The Simple Way To Connect Existing Apps to Public Cloud

Alex Ellis

Learn how to use a Hybrid Cloud model to connect your existing apps to the Public Cloud using private tunnels.

Introduction

Over the last 15 years, I’ve seen more and more companies migrate applications away from their own physical servers to public cloud. Jokingly, “public cloud” is also known as “someone else’s computer”, but this does detract from the value of a hosted service. The Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) and all on-going costs such as hardware maintenance, capacity planning, onboarding new servers and decommissioning all become someone else’s problem.

At the beginning of my career, I saw one application being deployed to a single server, and if there were two separate applications or customers that needed hosting, it would mean two servers. Virtual machines and hypervisors like VMware ESXi and Microsoft Hyper-V meant that one server could securely host several different applications, but the servers were still managed in a very manual and time-consuming way. Then in around 2014 with the advent of containers and the popularity of microservices, I saw an accelerated move to the cloud for many companies.

Today, in 2021, it would be very surprising to see a newly formed company decide to build their own datacenter and host their own servers instead of building directly upon a public cloud.

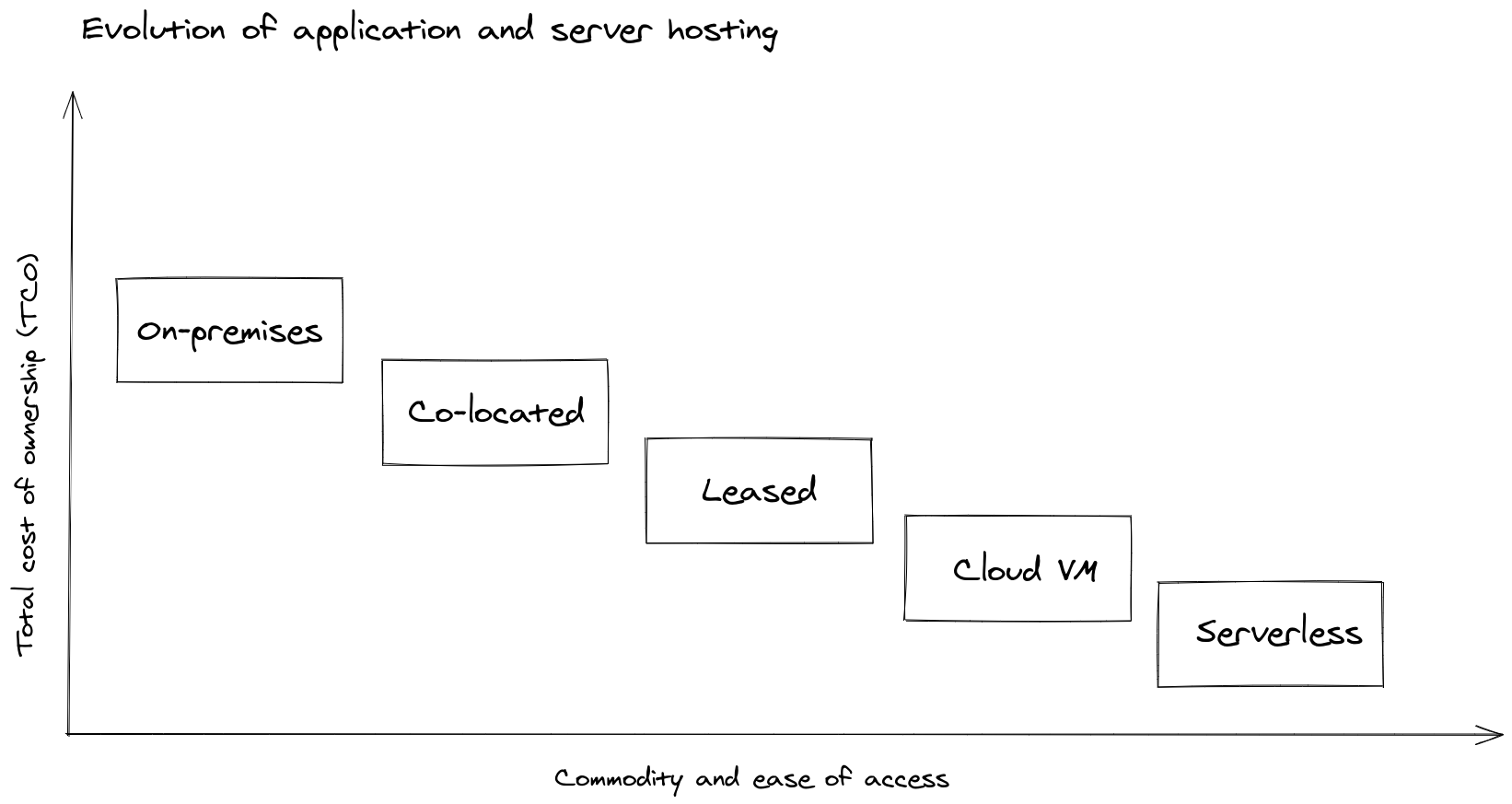

Pictured: TCO vs. ease of use

Whilst running services in a private data-center gives maximum control, and governance for a company, the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) can be higher. This is especially true for up-front costs. Managed compute platforms like AWS EC2 can give the impression of unlimited resources being available to your teams, through a simple Application Programming Interface (API).

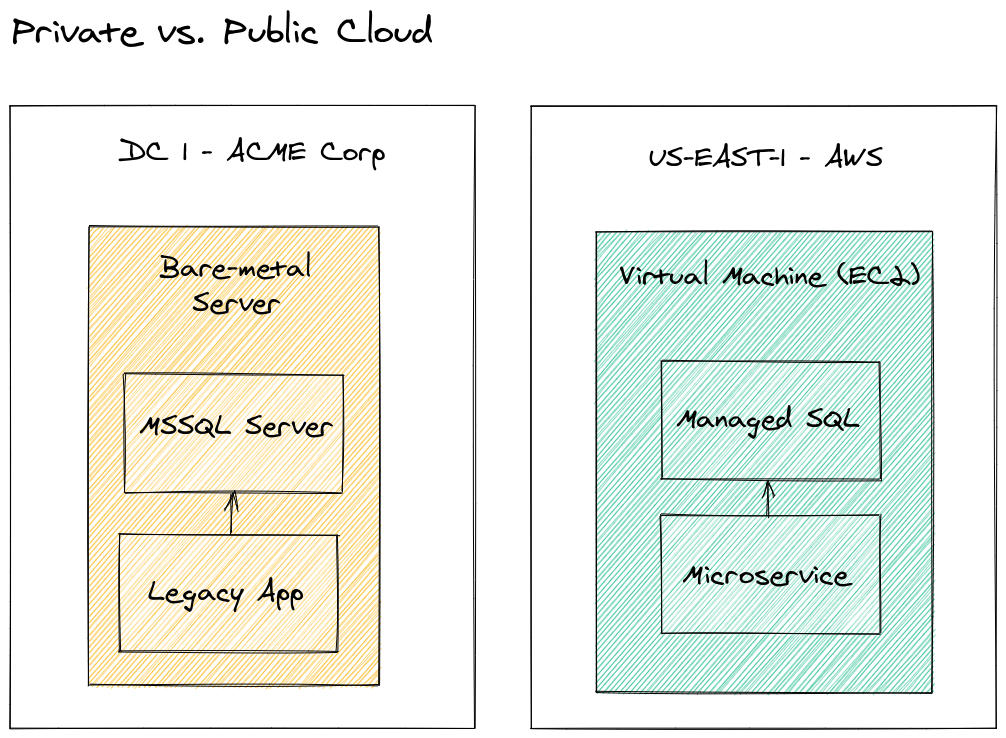

Pictured: the same application on private and public cloud.

For companies that are not starting over, you may already have some legacy or traditional apps running in your own datacenters. This is perfectly normal, and in certain scenarios like in defense, or banking, this may be a regulatory requirement. It may be that the application is running on an outdated platform, that would be hard to migrate, or that something which “isn’t broken” would require a significant cost to move to the cloud.

IT managers would traditionally turn to VPNs to bridge a private and public cloud and cloud companies have purpose-built services for this use-case such as AWS Direct Connect. In some circumstances, you may even have to pay for a direct line to be connected between your datacenter and the nearest cloud region.

Unfortunately, VPNs tend to have a bad reputation for being complex to configure and time-consuming to manage over time. Clients have told us that they want to avoid VPNs at all costs and OpenVPN tends to be one they love to hate. Recently a client told me that they have to send an engineer on-site at ~ 800 EUR / day to configure VPNs for each of their customers. They also shared that customer IT departments often resist the need to open up the necessary UDP or TCP firewall ports for VPNs.

Simple hybrid cloud

In an ideal world, we would move all of our services to the public cloud, but many systems cannot be moved, or are not a good fit for a lift and shift due to concerns over governance.

My definition of Hybrid Cloud is simply having parts of your system in a private datacenter or on-premises, and other parts on a public cloud platform.

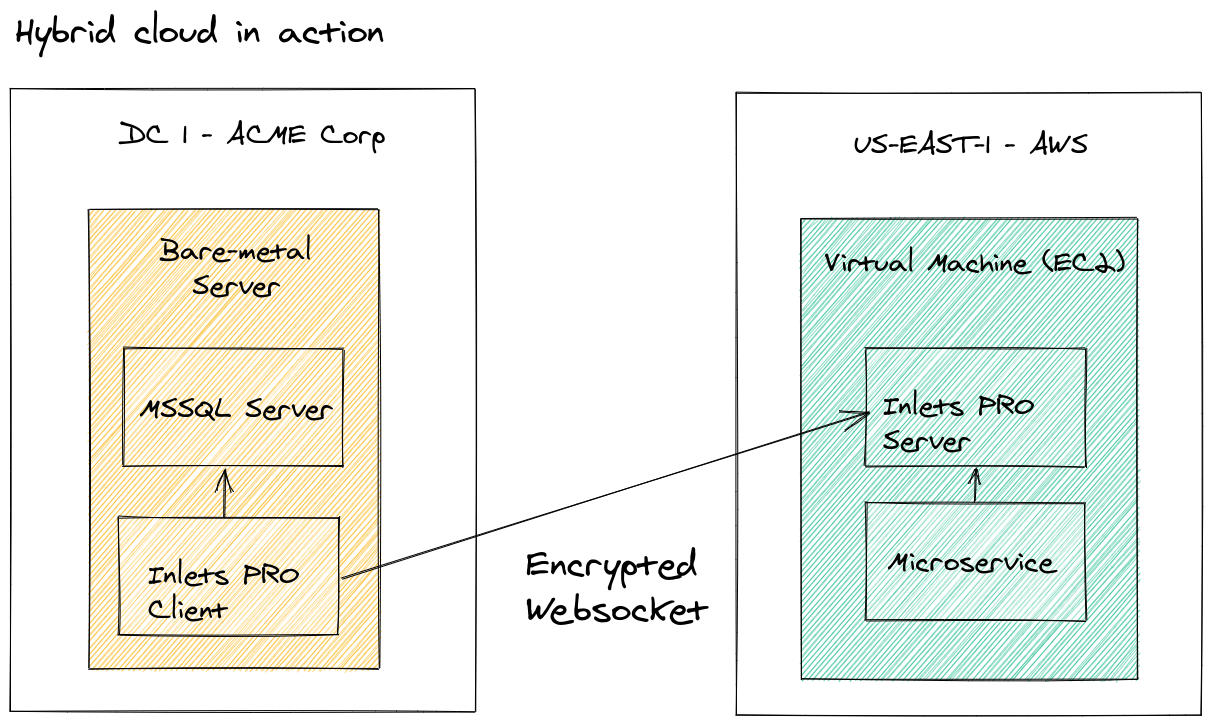

Hybrid Cloud in action using an inlets tunnel to access the on-premises database

In the diagram above, we can see that the Legacy app has been migrated to a cloud microservice and deployed to the US-EAST-1 region on AWS Cloud. The database, however was a version of Microsoft SQL Server that is not available on AWS, and runs on a Windows Server, which has so much data, it’s not practical to migrate it. So a secure tunnel is established between the two services, and the microservice is able to access the on-premises environment without it being migrated.

Wait, is that secure?

I know what you’re thinking. Is that service exposed on the Internet? Is it encrypted and what level of authentication is in place?

The answer is that the tunnel server has two parts, a control-plane and data-plane. The control-plane is an encrypted websocket with authentication, which the inlets-pro client connects to. This is normally port 443 or 8123, and can pass through the firewall without opening ports because it uses an outbound connection. It can also pass through a HTTPS proxy, to keep the IT team happy.

The data port for SQL server would be TCP/1443, which will not be exposed on the Internet. It will only be available within the Virtual Private Cloud (VPC) or private LAN adapter on the remote machine. It would be trivial to restrict access even further to a given IP whitelist or subnet.

So when the microservice needs to speak to MSSQL to run a Stored Procedure, or a SQL statement, it connects to the inlets-pro server process, which in turn exposes the port of MSSQL (1443). The server then asks the inlets-pro client to forward the connection to the on-premises SQL server. There will be some additional latency, given that these two services are not within the same LAN, but otherwise, the experience should be comparable to a VPN, but much easier to set up.

Another client recently asked me whether DICOM, a legacy TCP protocol for medical image processing could be sent securely over an inlets tunnel. The answer was yes, because even though the version of DICOM they were using had no TLS awareness, the inlets socket is encrypted between the client and the server.

We’ve also recently seen an interest in monitoring multiple Kubernetes clusters from a single central cluster. Of course it is also possible to federate an on-premises service directly into a Kubernetes cluster.

Another use-case for hybrid cloud that we’ve heard about from customers is federating users for applications using a private Identity Server using OpenID Connect. In this case, public cloud users can use Single-Sign On and existing corporate credentials to access systems.

Setting up a private tunnel is simple as binding the data-plane to loopback or a private LAN IP address. Note the --data-addr flag.

export TOKEN="secure"

export PUBLIC_IP=""

inlets-pro tcp server \

--auto-tls \

--data-addr 127.0.0.1 \

--auto-tls-san $PUBLIC_IP \

--token $TOKEN

Then connect a client with a Windows, Linux or MacOS binary:

export TOKEN="secure"

export PUBLIC_IP=""

export UPSTREAM="localhost"

export PORTS="1443"

inlets-pro tcp client \

--url wss://$PUBLIC_IP:8123 \

--token $TOKEN \

--upstream $UPSTREAM \

--ports $PORTS

If you wanted to run the tunnel client on another machine on the private cloud, you can change the --upstream flag to any reachable hostname or IP address. You can also forward additional ports if you need them like SSH, VNC or RDP over the same tunnel.

Do you want to try tunnelling a database for yourself? You can try the following tutorial: Tunnel a private database over inlets PRO

Wrapping up

We covered the progression and move away from on-premises datacenters to modern VM or microservice-based architectures. Then we showed how tunnels could be used to securely connect private clouds to the public cloud. Do you have questions or comments?

I’d be happy to chat to and see if we can help you access your legacy systems from your public cloud platform.

Taking things further

Subscribe for updates and new content from OpenFaaS Ltd.

By providing your email, you agree to receive marketing emails.